- Home

- William Miller

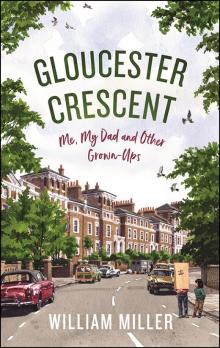

Gloucester Crescent

Gloucester Crescent Read online

GLOUCESTER CRESCENT

William Miller is a television producer and media executive. His long career in television has included time as head of talent at BBC Worldwide, and he has worked with Nigella Lawson, Brian Cox, The Hairy Bikers, Kirstie Allsopp, Phil Spencer and many more, to help build their brands, businesses and develop their TV shows. In 2009 William returned to Gloucester Crescent where he now lives with his wife and two teenage daughters, three doors from his parents.

GLOUCESTER CRESCENT

Me, My Dad and Other Grown-Ups

WILLIAM MILLER

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © William Miller, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 440 3

For Trine, Daisy, Stella and my parents, Rachel and Jonathan

CONTENTS

Prologue (Age 53)

Part One: August 1975 (Age 11)

Part Two: August 1980 (Age 16)

Part Three: September 1982 (Age 18)

Epilogue (Age 54)

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

PROLOGUE

Autumn 2017 (Age 53)

When we were children, my father would take me and my brother up Primrose Hill. At the top he’d look out across London, and tell us how he’d spent his life moving very slowly around Regent’s Park, and had never lived anywhere else. With his arm outstretched he’d take aim, squinting, his cheek resting on his arm, and draw a line across the city with his great big index finger. Pointing at a crescent of tall white houses at the bottom of Regent’s Park, he’d tell us that this was where he was born. His finger would move over the park to St John’s Wood, where he lived before and after the war. Dropping to the bottom of Primrose Hill, he’d point at the big bird cage in London Zoo, whose designer, Cedric Price, was best man at his wedding. Then he’d swing back to the other side of the hill and to the mouldy basement flat on Regent’s Park Road where he and my mother moved after they got married. Finally, his finger would arc up over the rooftops of Chalcot Square and across the red-brick walls of my primary school on Princess Road. When he stopped, he would be pointing to where a mass of green trees explodes between the roofs of a circle of tall houses. Holding his finger steady, he’d smack his lips and say, ‘And this is where we are now – Gloucester Crescent. You see, we haven’t gone very far in all that time.’

The events in this story are a lifetime ago. More than forty years have passed, and I am married with my own family to take climbing up Primrose Hill. But the memories of my childhood and the community I grew up in are as vivid as ever. My parents moved to Gloucester Crescent in the 1960s, and over the next three decades great friendships were forged, hearts were broken, professional rivalries were fuelled and needless fallings-out took place as the celebrated occupants of Gloucester Crescent came together and allowed their lives to become entwined.

As children, we were free to roam across the back gardens and wander in and out of our neighbours’ houses. We explored, climbed trees and leaped over walls, spent hours in each other’s homes and crossed the invisible boundaries that our parents unconsciously created with their rivalries. My closest friends had parents much like mine: most had been educated at the same small collection of public schools and knew each other well from either Oxford or Cambridge and then through their work. Together they’d found a common and worthy cause to believe in, born out of the post-war euphoria of the 1945 Labour landslide, which created a radical new way of thinking: full employment, a cradle-to-grave welfare state and a national health service that would be free to all. The promise of a fairer society led our parents to become left-leaning, idealistic as well as anti-establishment, with a strong distaste for the old-school approach to authority and power. They made the conscious decision to give their children a radically different childhood from their own. We were sent to the local state schools, where we could mix with children from every walk of life, and were encouraged to be free spirits. They frequently left us to our own devices while they went off and expanded their utopian vision and pursued glittering careers. We all looked up to our gifted parents and hoped that one day we might be like them, but as we got older many of us found ourselves left behind and struggling to keep up. It began to seem that we’d been part of an experiment driven by their principles, rather than their care. Despite the huge privilege of our birth, we were left feeling bewildered, and a few of us, like me, longed to escape to a way of life that was more structured and conventional.

Within this community and at the centre of the story are my parents, Jonathan and Rachel Miller. An ever-present figure in our home was their close friend (and one of my father’s three partners from Beyond the Fringe) Alan Bennett, who started off living in my parents’ basement and then bought the house across the road. Other friends in the street were the jazz singer and writer George Melly and his wife, Diana. In the mid-1970s the Mellys sold their house to another friend, Mary-Kay Wilmers, the ex-wife of the film director Stephen Frears. She later took over the editorship of the London Review of Books from my maternal uncle Karl Miller. Across from the Mellys were the artist David Gentleman and the Labour MP Giles Radice and, two doors away, the writer Claire Tomalin and her journalist husband, Nick. He was killed in Israel in 1973 by a Syrian missile while reporting on the Yom Kippur War, and she later married the playwright Michael Frayn, who in turn moved into the Crescent.

Immediately behind us, in Regent’s Park Terrace, were the eminent philosopher Sir A. J. Ayer (known to his friends as Freddie) and his American wife, the author and broadcaster Dee Wells, along with their son, Nick, and her daughter from a previous marriage, Gully Wells. Next to them were Shirley Conran and her sons, Jasper and Sebastian. Further along the Terrace were the writers Angus Wilson, V. S. Pritchett and A. N. Wilson. Across the road from us and next door to Alan Bennett were the novelist Alice Thomas Ellis (aka Anna Haycraft), her publisher husband Colin Haycraft and their six children. Colin’s publishing house, Duckworth, was based in an old piano factory rotunda at the top of the Crescent. They published many of my parents’ friends, including Oliver Sacks, Beryl Bainbridge, the American poet Robert Lowell (who was also my godfather) and his wife, Caroline Blackwood. Three doors from our house was Sir Ralph Vaughan Williams’s widow, Ursula, and across the road from her the artistic director of the Royal Court, Max Stafford-Clark, who lived with his wife, Ann, and the son she had with Sam Spiegel, the producer of films like On the Waterfront, The African Queen and Lawrence of Arabia. There was also Miss Shepherd, the eccentric homeless woman who in the late 1960s arrived in the Crescent in her van and stayed for twenty years. After several years of moving her van up and down the Crescent, she eventually parked it in Alan Bennett’s driveway, where she remained until she died in 1989. In nearby streets were others in my parents’ circle, such as the documentary film-maker Roger Graef, Kingsley Amis and his son Martin, Beryl Bainbridge, Sylvia Plath and Joan Bakewell.

Most of the time our parents were happy to share their homes and meals with their friends in the street, but relationships occasionally became strained when they eithe

r wanted to sleep together or to kill each other. To the outside world it was a community that seemed to operate as if it were a closed society. It was often misunderstood or maligned by its critics and became the focus of much mockery in the press and on television. But it was my home.

As a child who was overshadowed by these extraordinary people, I longed to have a voice and be heard. Whenever I could, I went in search of the grown-ups who would tell me their stories and listen to my thoughts about the world as I knew it.

This is that boy’s story of Gloucester Crescent. Sandwiched between the bustling chaos of Camden Town and the leafy tranquillity of Primrose Hill, I did everything I could to get away from it, and when I did finally leave, I thought I’d gone for good. But things don’t always go the way you think they will, and to my surprise I’ve ended up right back where I started. Having returned, I find myself doing exactly what my father did all those years ago: sitting at his desk staring out the window thinking about life when he should have been writing.

Kate, me, Tom and Mum, Antibes, 1971

When I was a child, I’d listen to the rhythmic clatter of manual typewriters coming from the open windows of houses along the street. Staring out of my study window, I can see why some, like my father, lost their train of thought as they sat at their desks and got distracted by life in the gardens: the sounds of children at play, grown-ups chatting and laughing and then the views across the dense foliage that bursts into life each spring. The branches of the vast London plane trees heavy with leaves that sway in the breeze, sending hypnotic ripples of reflection over the windows of the tall houses in the terrace opposite.

Now, over four decades later, I have the ghosts of my past to distract me as well. Occasionally, I am sure I see something moving out of the corner of my eye – a child in the garden racing down the back steps of a house opposite. He crosses the garden and then vaults effortlessly over the wall, but then I look up and there’s no one there, just a single cat slipping quietly through a bush that overhangs the wall.

PART ONE

August 1975 (Age 11)

Mum, me and Tom, back garden at Gloucester Crescent, 1975

1

COMPETITIVE TYPING

The best thing my parents ever did was to buy our big old rambling house in the Crescent. I’m not sure we’d be known as ‘the Millers’ if we lived somewhere else. Maybe we’d just be that family up the road with the blue front door. Pretty soon after they bought the house Mum and Dad turned it into the perfect family home, even though at the time they didn’t have any children. Now they have three, and the house is always filled with people, who come and go all day long, and in some cases, come and then stay for ever.

In the middle of all this coming and going is one thing that never changes and I hope never will: my Mum – she’s lovely, pretty and warm and the person who holds it together for all of us. She’s the rock everything in our lives is built on. She makes it possible for us to go to school in the morning, and then, when we come back home, we find everything we need is there. I know if it was left to Dad we’d stay up past midnight, never get to school on time and we’d probably all starve. He couldn’t be more different from Mum, who, for starters, doesn’t think the whole world is against her. Dad’s a bit like our television – everything is in black and white: he either loves you or hates you, and people are either good or bad. It’s a bit like his politics, where everyone is either a nice kind Labour person or an evil and cruel Tory. Much of the time he’s far too busy with work and his big ideas to think about family life and leaves Mum to deal with all that. His head is filled with getting on with writing for a book or magazines (which he doesn’t seem to like), travelling and directing plays and operas and having to go on the telly. Before I was born, he was a comedian, and before that a doctor, but he gave that up and never stops telling us how much he wishes he hadn’t.

Mum gives him the freedom to do all these different jobs and makes it possible for him to try new things with his work. This sometimes means he goes away for weeks or months. And he does it knowing that, when he comes home, life in the Crescent will be exactly as he left it. I think lots of the dads in the street are like this and seem to live on another planet from their families. An American friend of Mum and Dad’s, who I’ll tell you about later, always says, ‘The dads live on Planet-Do-I-Give-A-Shit’, but I think the lucky dads are the ones who were sensible enough to marry mums like mine.

Mum and Dad met at school, when she was 16 and he was 18. Mum was really pretty, whereas Dad was tall and gangly with curly red hair and I don’t think knew much about girls. It’s no surprise that he fell madly in love with her the minute he saw her, but she wasn’t interested in him at all. In fact, she thought he was a show-off, and it took a lot of work for him to convince her he wasn’t. I think he was also a bit hopeless at courting and would turn up to take her out with his two best friends from school, Oliver Sacks and Eric Korn. She eventually changed her mind after Dad went to Cambridge and she went to see him in a comedy show where he was on stage dressed as Elizabeth I in sunglasses. When she realised he was talented and quite funny, and even rather handsome, she thought it might be worth giving him another chance. I don’t think he’s stopped loving her ever since, and I know he would be completely lost without her. Dad isn’t the easiest person to be married to, and I’ve often seen her lose her temper with him or cry when things aren’t going well. What’s amazing is that, with all she has to take care of and in spite of all the comings and goings and the number of people who turn up unannounced at the kitchen table, she also manages to be a hard-working doctor. She has all these patients who phone up in the middle of the night and make her go out and see them when all they probably have is a cold or a headache.

Mum, 1954, age 18

Dad, 1954, age 20

When Mum and Dad first got married, they moved into a damp basement flat on Regent’s Park Road in Primrose Hill. They were happy there until Dad’s books started to go mouldy with the damp and they decided they had to move. They couldn’t really afford to, but Mum’s Great Aunt Brenda gave them some money to help them buy a house of their own. At the time Dad was doing a comedy show in the West End called Beyond the Fringe with Alan Bennett and two other friends called Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. According to Dad, everybody really liked the show, so he went to the bank with all the reviews from the newspapers, thinking that they might convince them to give him a loan. It worked, and the man at the bank lent him some money. With Great Aunt Brenda’s money and the money from the bank they were able to buy our house in Gloucester Crescent. Dad’s not very good with money, so borrowing it gave him sleepless nights. I told my best friend, Conrad Roeber, who lives two doors from us, that our house cost a million pounds. I thought that seemed like a fair price because I imagined that’s what most big things grown-ups bought probably cost. Conrad believed me, but his older brothers just laughed, so I felt a bit stupid when Dad told me it only cost £7,000. Mum and Dad didn’t have children yet, so the house must have seemed enormous and bigger than anything they ever thought they would own.

Dad’s one-man show, Poppy Day, Cambridge, 1953

I’ve always thought Gloucester Crescent is one of nicest streets in London. It’s filled with tall houses that sit on either side of a road that slopes down a hill. Joining one end of the Crescent is another street with a row of identical houses called Regent’s Park Terrace. These look over the backs of the houses on our side of the Crescent, which means we can see the people who live in them and they can see us. Between these two streets is a big jungle of gardens, which are divided by brick walls with a long one that runs all the way down the middle. Although it’s quite high, for kids it’s a bit like a path that connects all the gardens.

Dad shortly after buying the house in Gloucester Crescent, 1961

Gloucester Crescent, 1975

Half-way down the Crescent at the bottom of the hill is Inverness Street, which comes off it like the branch of a tree. It takes you t

hrough a fruit and veg market, and at the end is another world – Camden Town. You see all sorts of people there: rich and poor, black and white, Indian, Greek and a lot of Irish. Wandering around in the middle of it are the families who have come out of the Underground station and are looking for London Zoo. They always seem a bit shocked as they step over the scruffy old men (and sometimes women) lying in doorways, asleep or drunk on cider.

If you walk in the other direction from Gloucester Crescent, you won’t believe how different it is: a few streets away is Regent’s Park, with enormous and very grand white houses around the edge. And then there’s Primrose Hill.

I can’t tell you how many times Dad has taken us up Primrose Hill and done exactly the same thing. We get to the top of the hill and he starts telling us about how he’s lived his whole life near Regent’s Park. I don’t mind him repeating himself as I like hearing about it. I love where we live and, most important, I like the fact that we have never moved from here, and I hope we never will.

Plus, Primrose Hill is my favourite park and has been for as long as I can remember. I’ve pushed my bike up the steep path to the top with Mum, Dad or my friends, and when it snows I’ve tobogganed with Tom and the Roebers from the top all the way to the very bottom at terrifying speeds. Primrose Hill is a proper green and grassy hill in the middle of a big city. If you climb to the top and don’t look back till you get there, it’s amazing and worth it when you finally do. Everything in London can be seen from the top of Primrose Hill. You can see all the way to Greenwich in one direction, and to the south there’s a really tall metal tower that comes out of the mist on the top of another hill. Dad once told us it was the Eiffel Tower, though I know it’s a lie – it’s the television mast at Crystal Palace, and it’s miles away. From here London looks much smaller than it is. It feels like you can almost touch the buildings that take so long to get to by car or on the bus or Tube, like St Paul’s Cathedral, Big Ben, King’s Cross Station, the Post Office Tower, Battersea Power Station and loads more.

Noble Intent

Noble Intent Noble Vengeance

Noble Vengeance Noble Sanction

Noble Sanction Gloucester Crescent

Gloucester Crescent Noble Man

Noble Man Noble Vengeance (Jake Noble Series Book 2)

Noble Vengeance (Jake Noble Series Book 2)